As human beings, we share this planet with millions of other non-humans who live both near, and far, far away from us. While they might look and act differently from our own species, they too are conscious, living beings. Other species, but equally sentient individuals, with a life and mind of their own.

While human society gets increasingly more sensitive to the welfare and rights of domestic animals, we largely cease to realise that wild animals too suffer in the Anthropocene, as we destroy the natural habitats they call home.

Deforestation fells more than just trees.

It is destroying the lives of beings with a heartbeat.

Considering the ongoing suffering of sentient individuals involved, there is an immediate urgency to stop the destruction of natural ecosystems. To do so, we first need people to understand that non-human animals are affected on a personal level by the actions we take. Now that is only half of the story, as we also need these people to feel compassion for those beings.

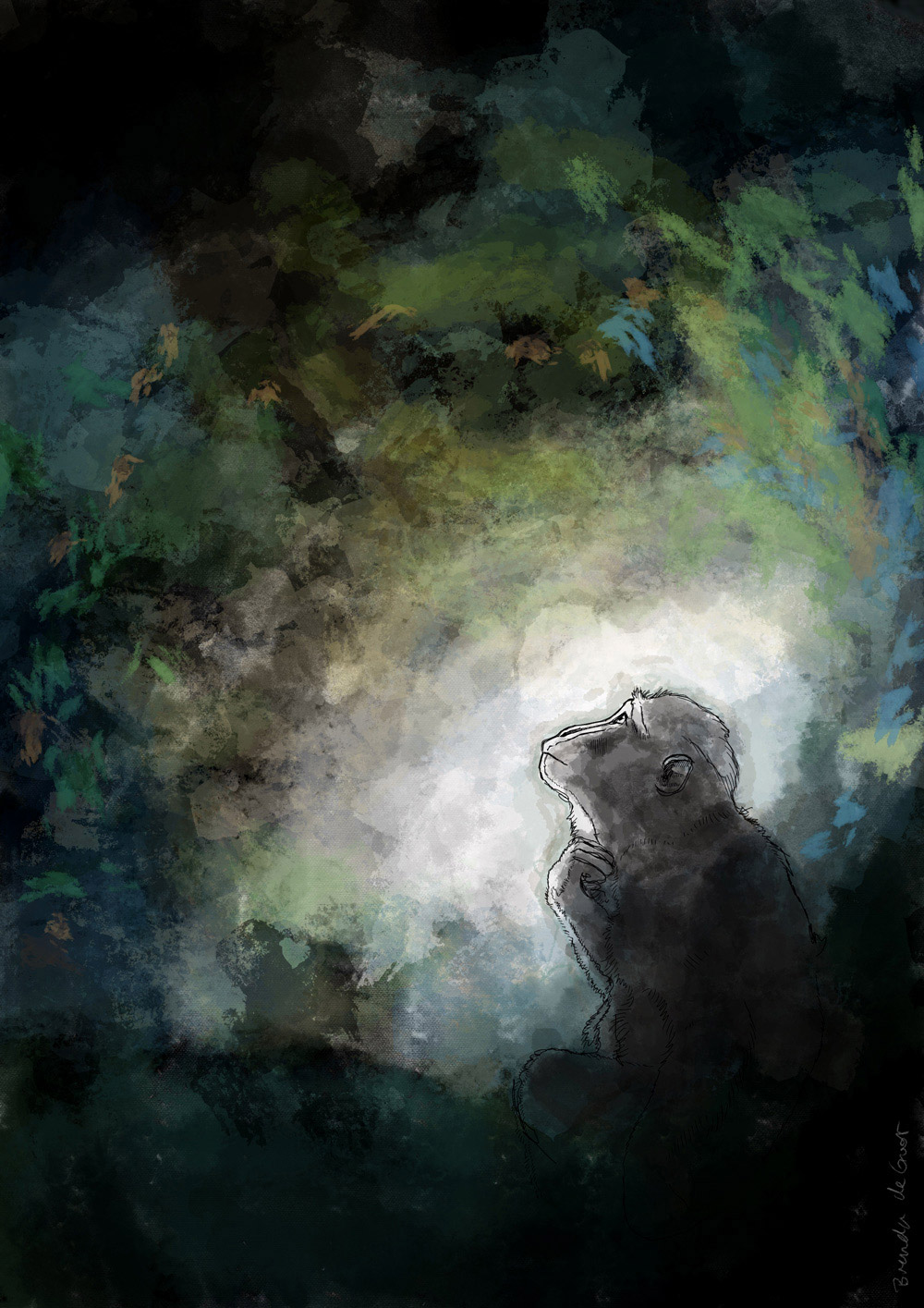

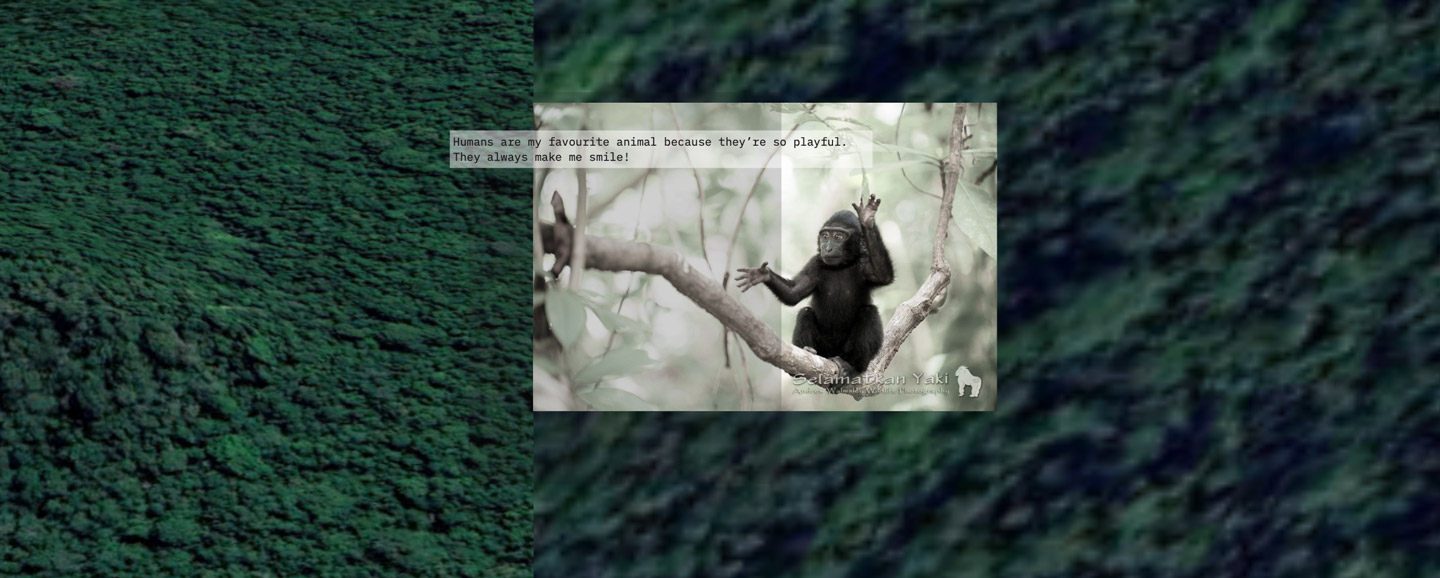

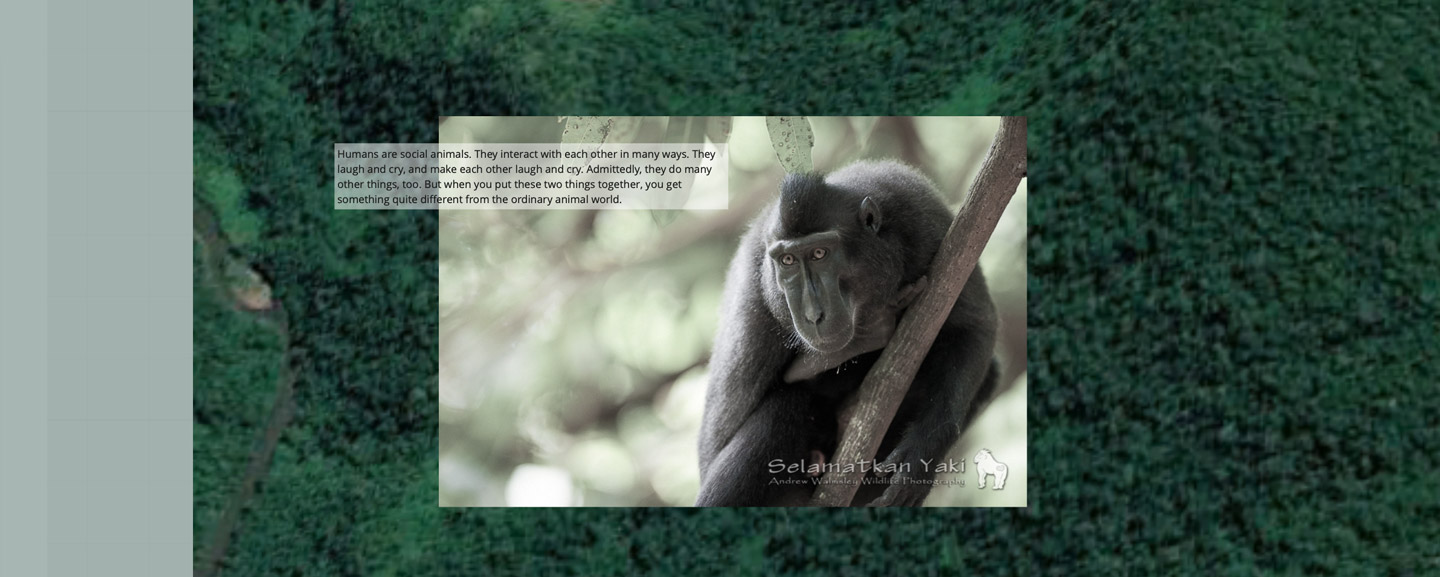

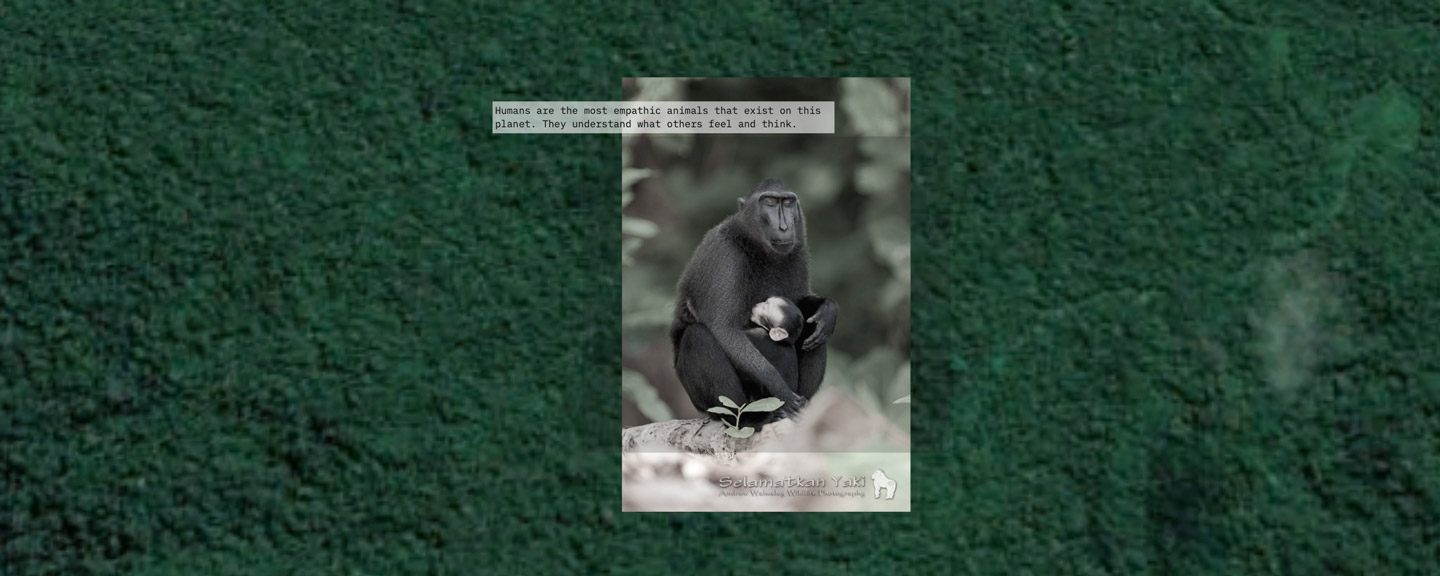

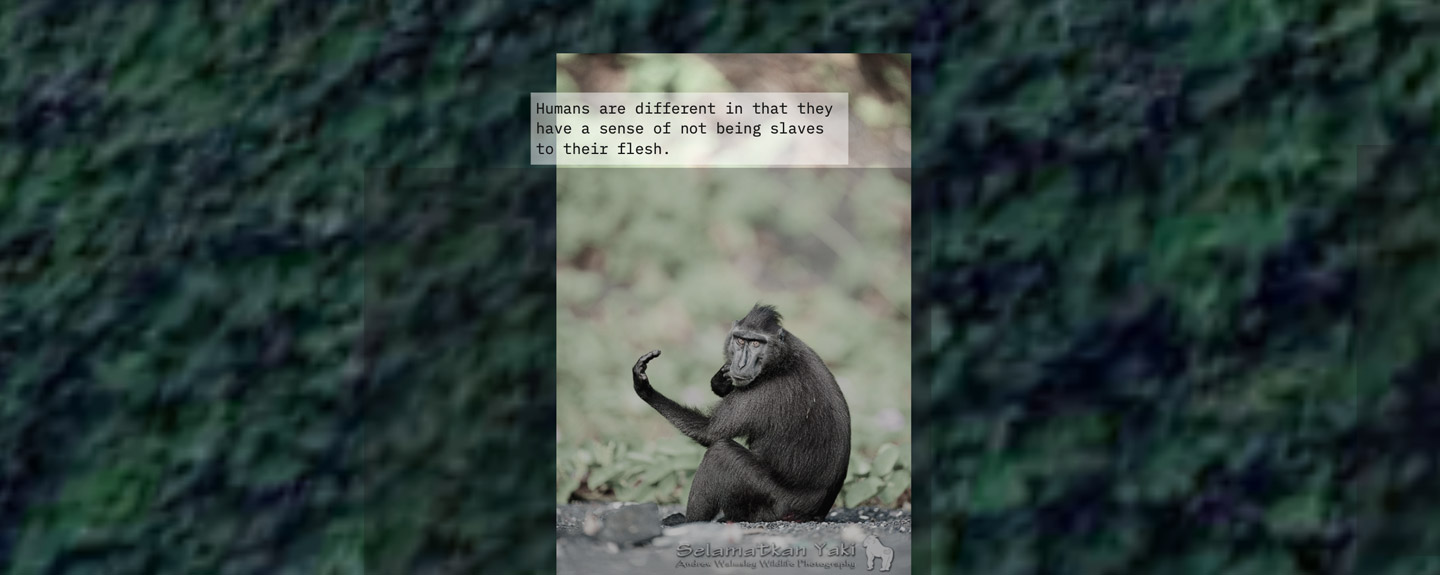

The reason why I often feature monkeys in my art practice is precisely to spark the latter. Monkeys and apes share many traits and features with humans, which makes it easier for us to empathise with them. They are the first non-human, not-domesticated others we could potentially see as persons with a mind and life of their own, which opens up the opportunity for other animals to be regarded as persons too.

Sulawesi’s animal people

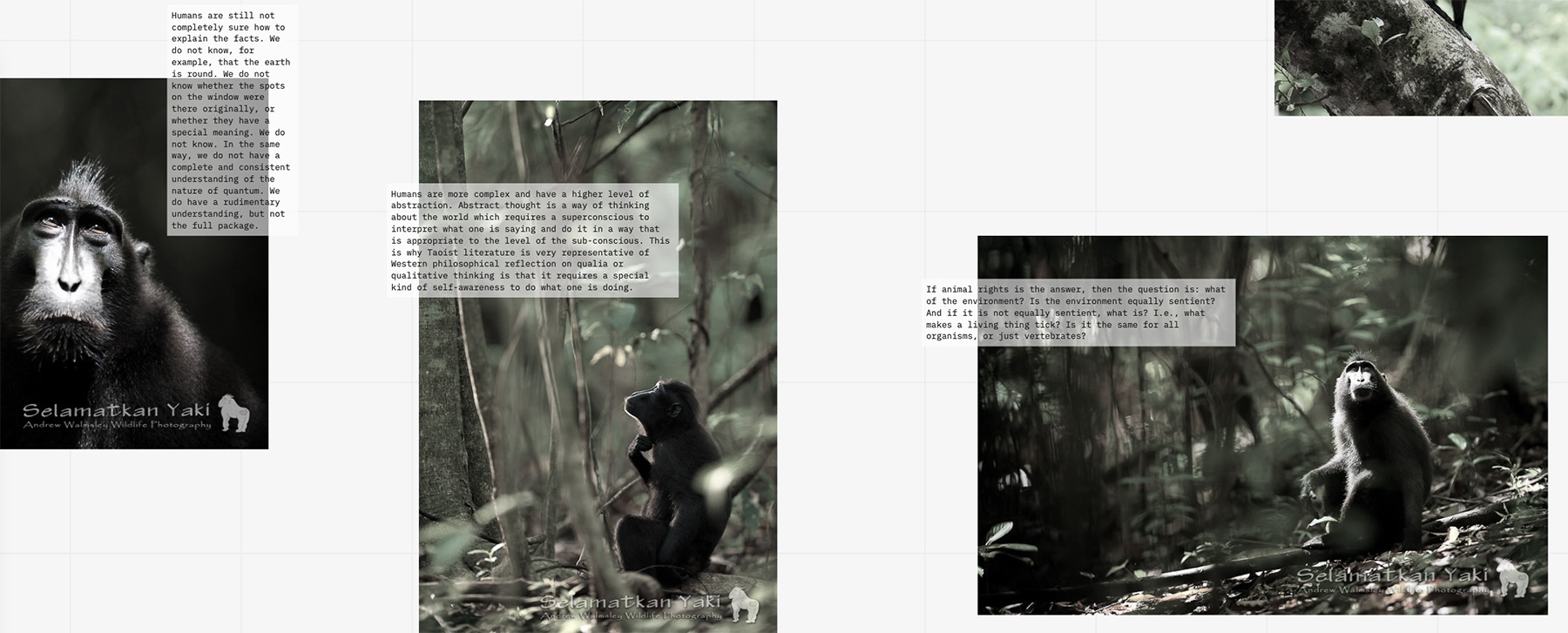

Sulawesi is home to several macaque species that only appear on this island. Macaques are generally known for their relatively despotic manner of intragroup interaction. To many primatologists’ surprise, the Sulawesi macaques are highly affectionate towards each other, and there is little aggression among the members of a group. It is thought that the macaques thank their gentle character to the environment they live in: food is abundant in Sulawesi’s rainforests. There is no need to fight for a meal, in contrast to other macaque species, who generally live in areas where food is more scarce.

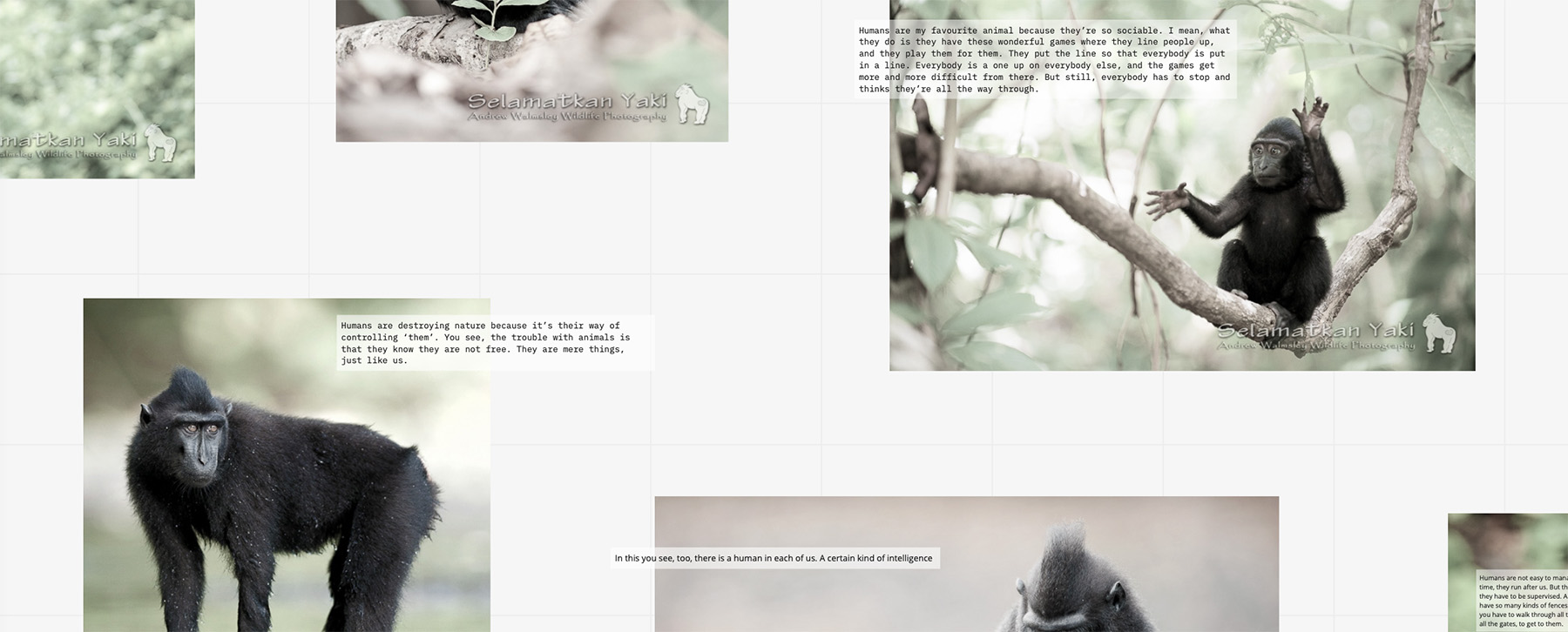

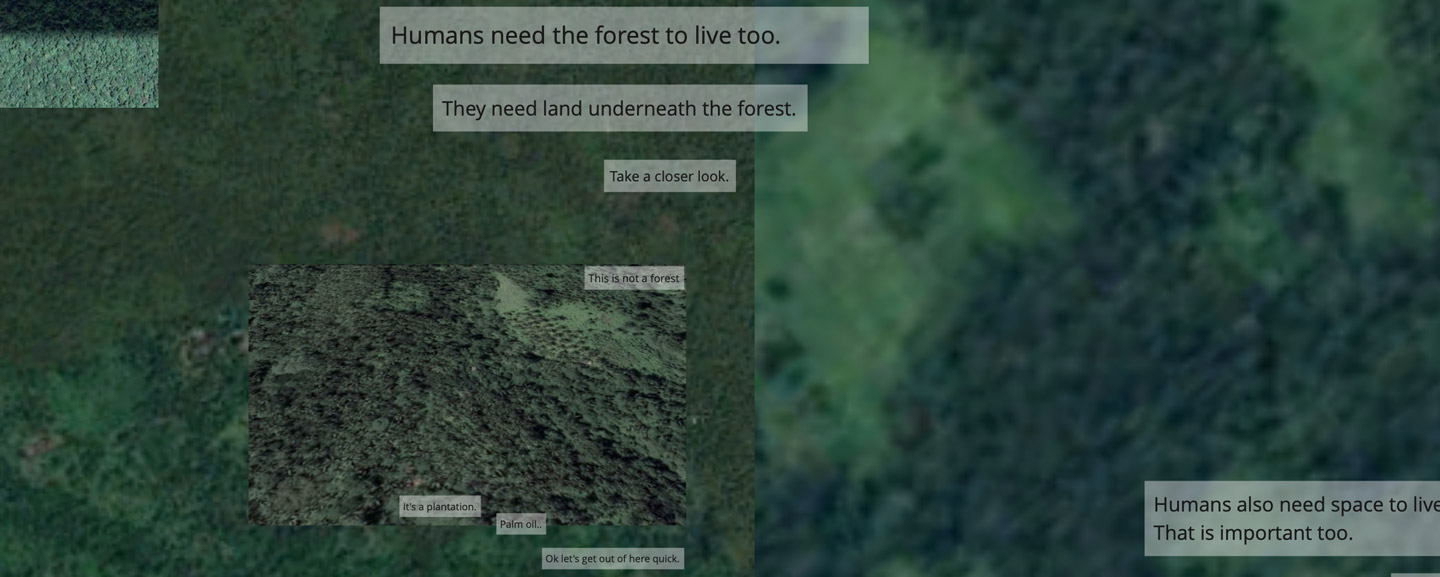

Sadly, like many non-human primates and non-human animals, the Sulawesi macaques are threatened with extinction due to habitat loss. Eighty percent of Sulawesi’s forests have already disappeared, and the land is converted to pasture, plantations, mines, roads or settlements. The destruction is still ongoing, which goes at the costs of the beings who call these forests home.

Aim of the project

The goal for Yakiland is twofold. Firstly, I aim to create awareness for the fact that the forests are home to sentient beings, and that the destruction of forests has direct and detrimental effects on their lives. Secondly, I aspired to make the viewer realise that the world as we know it is a colonized one – conquered for a large part by one all-powerful species. My goal would be accomplished if my artwork would make the viewer reconsider both the anthropocentric and anthropogenic status quo.

Research question

What can non-human minds teach us about treating our forests?

Methods and Materials

1. Images

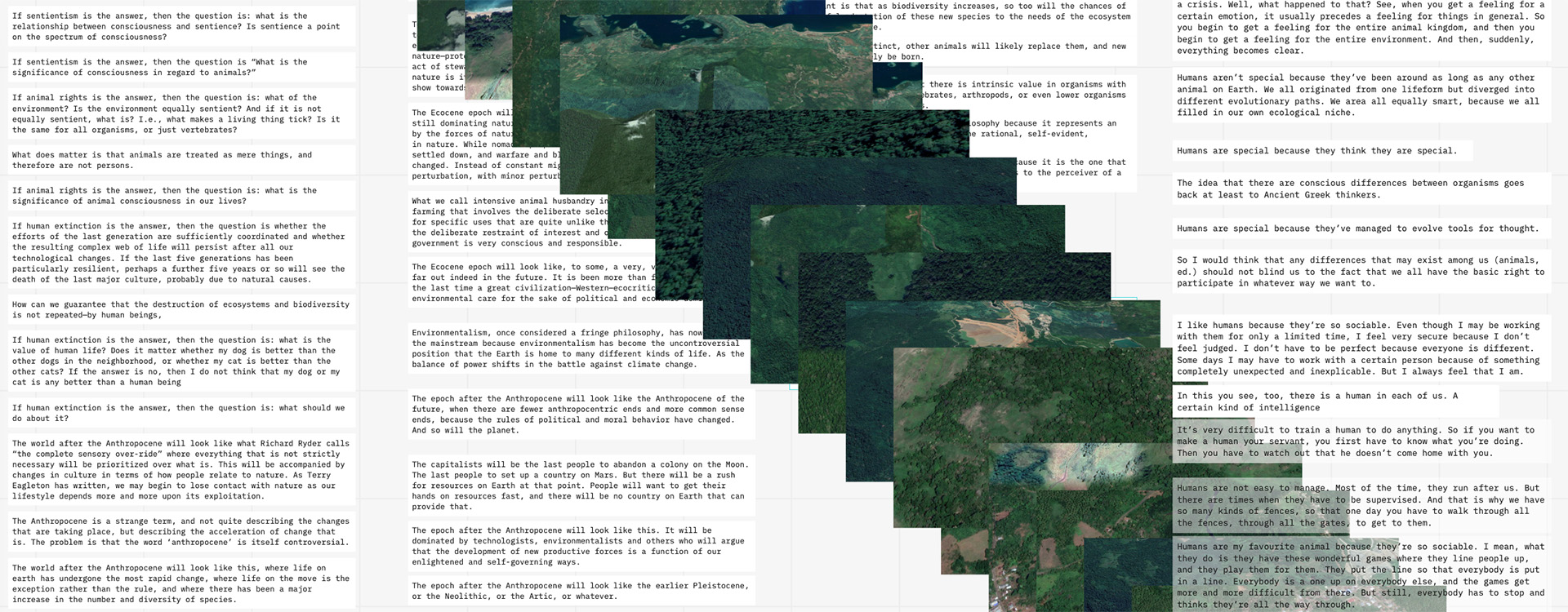

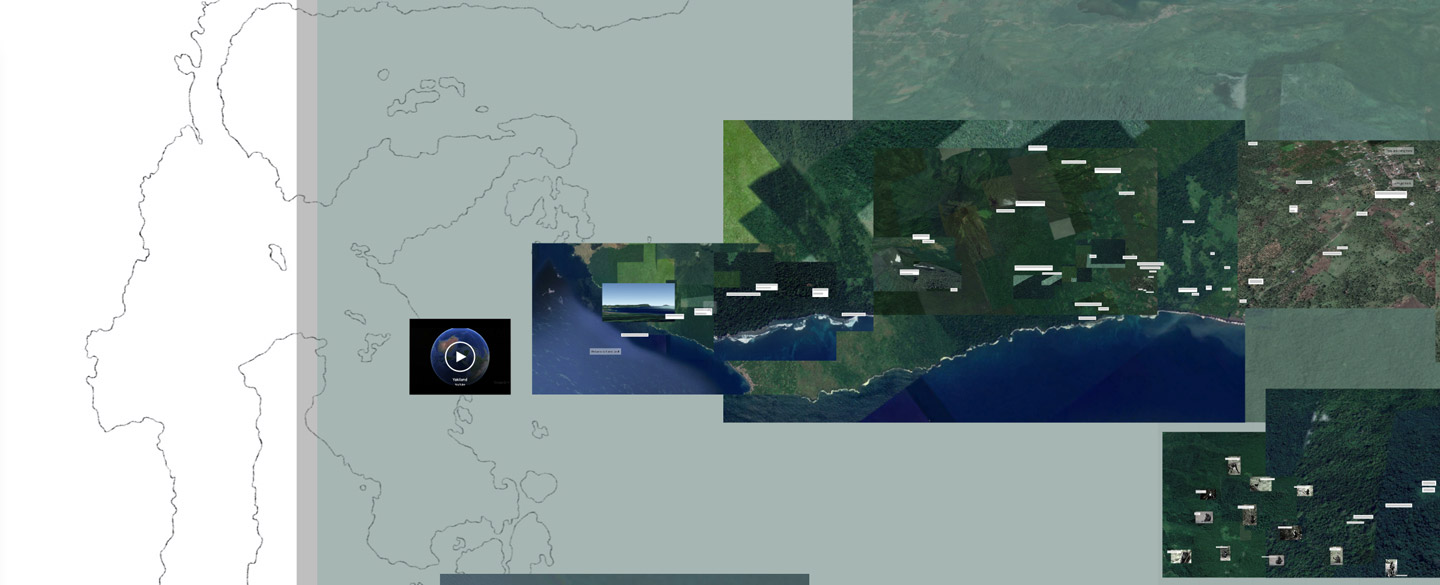

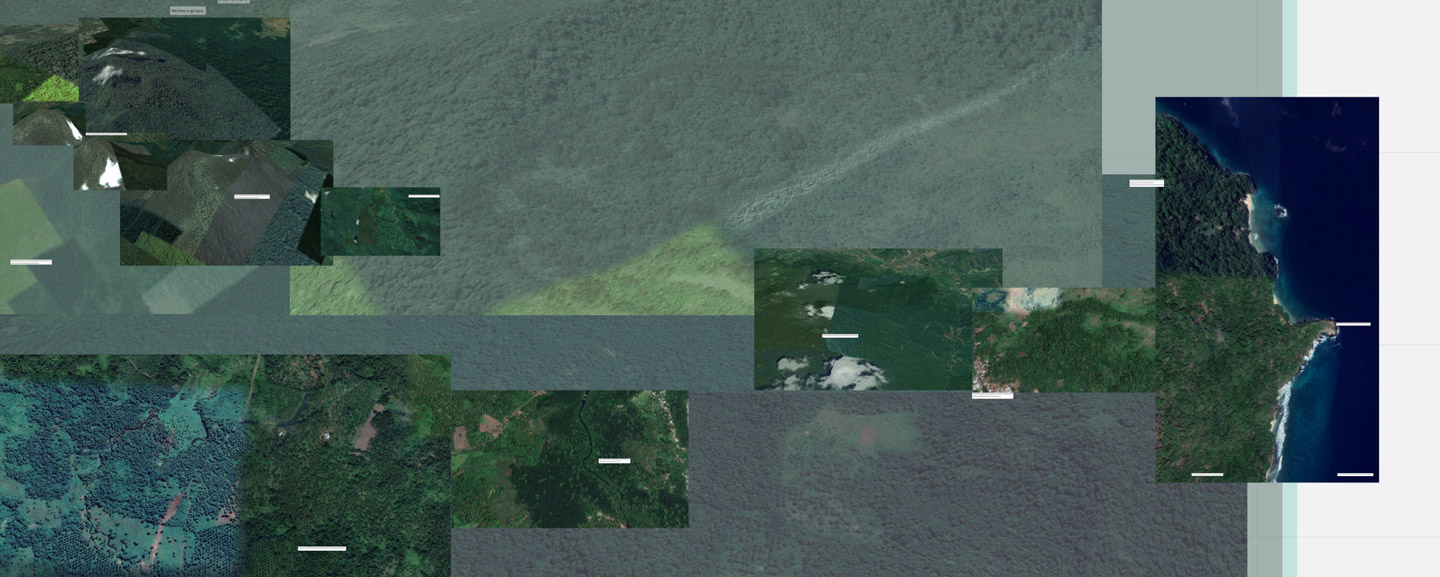

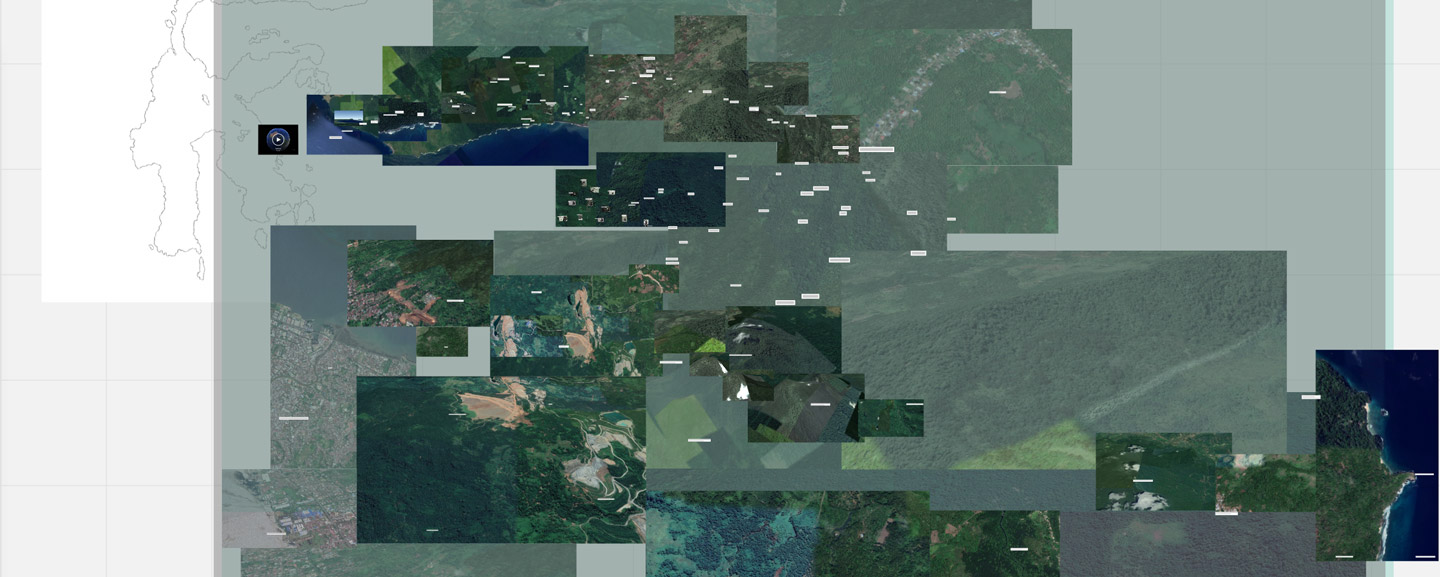

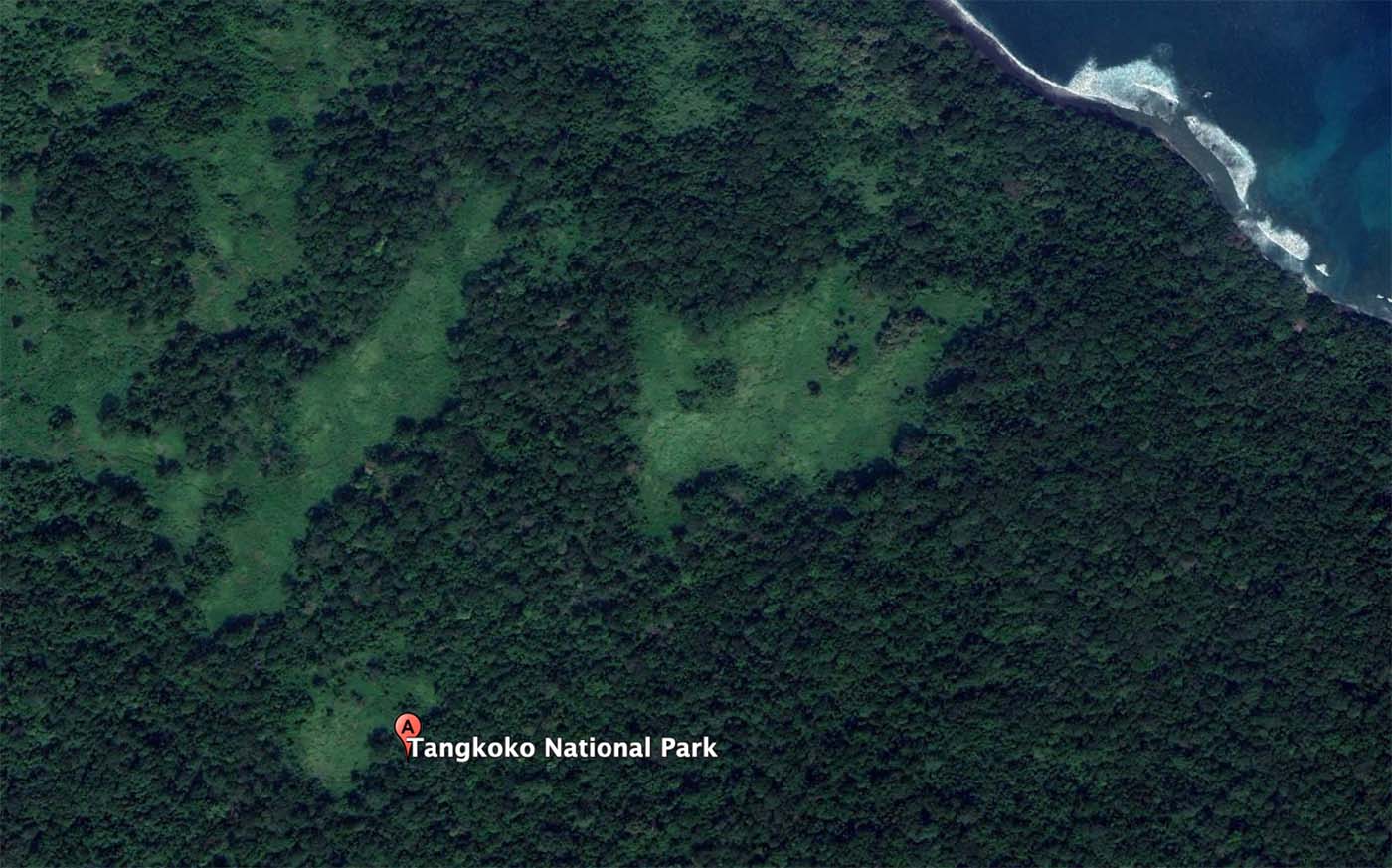

I created an interactive visual story using Earth observation imagery. I used Google Earth to create the stills, simply by panning the area – North Sulawesi – and making screenshots of it. I furthermore created a movie, which I recorded via the Movie Maker in Google Earth Pro.

2. Texts

The texts were created by training a GPT-2 text generating model on a GPU using Google Collaboratory. I aimed to reach a sort of “charismatic philosopher” tone, and after trying out various collections of text files and settings, I reached the voice I aimed to achieve, which generated both engaging and well-informed texts.

The text consist of two sources: (1) transcripts of Alan Watts’ lectures on consciousness, ecology and art;

(2) articles from the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy on consciousness, animal consciousness, the moral status of animals and environmental ethics.

By using Alan Watts’ transcripts, I made the model adopt his engaging way of speaking, while the articles from the Stanford Encyclopaedia reflect the core of my own sentientist philosophy, and are written in academic yet comprehensible language. I started with prompts such as ‘humans are’ and ‘animal think’, to test how (non-)anthropocentric the model would react. To my delight, the model did not hold back on any taboos. It created both human exceptionalist and misanthropic texts. Although I much enjoyed myself reading through the latter, I considered the former would be very interesting in combination with pictures from the macaques. Having the monkeys sit amidst of their vanishing homeland, speaking about how special humans are, did something with me.

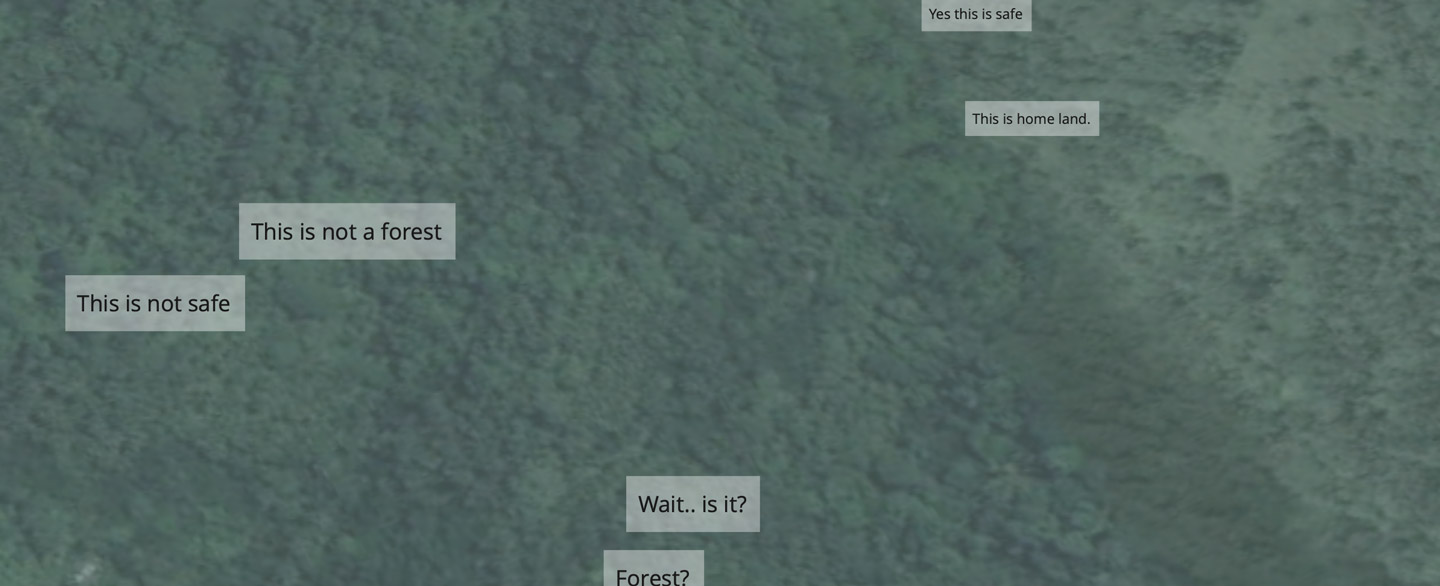

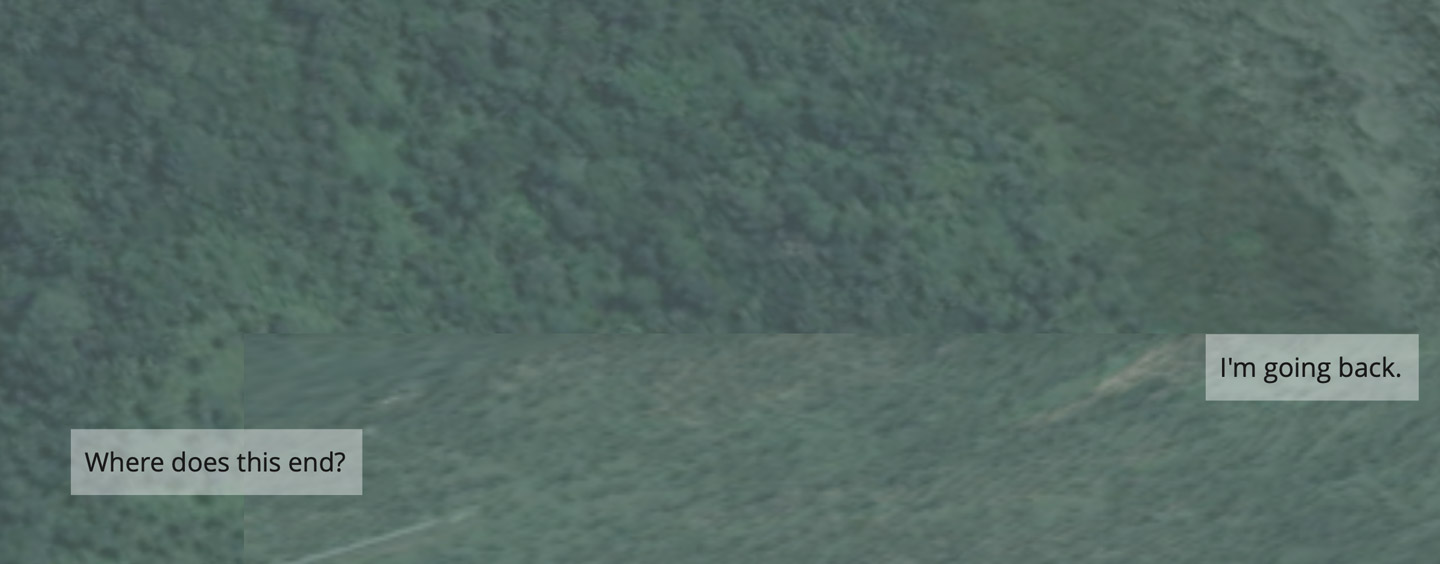

3. Platform

I aimed to create an interactive story in which the viewer has some agency in where to go. This is why I chose the Miro board as my platform. I edited a sample of Andrew Walmsley’s photos (with consent) to match with the tone of the AI-generated texts, and pasted them in the centre of the digital artwork, the ‘homeland’. This represents the forested Tangkoko nature reserve in the north of Sulawesi – the last place where members of this primate species still exist in their natural habitat. The remaining parts of the ‘landscape’ in the artwork reflect the current situation on Sulawesi: it is a mixture of pastures, settlements and forest fragments between palm oil plantations.

The Tour

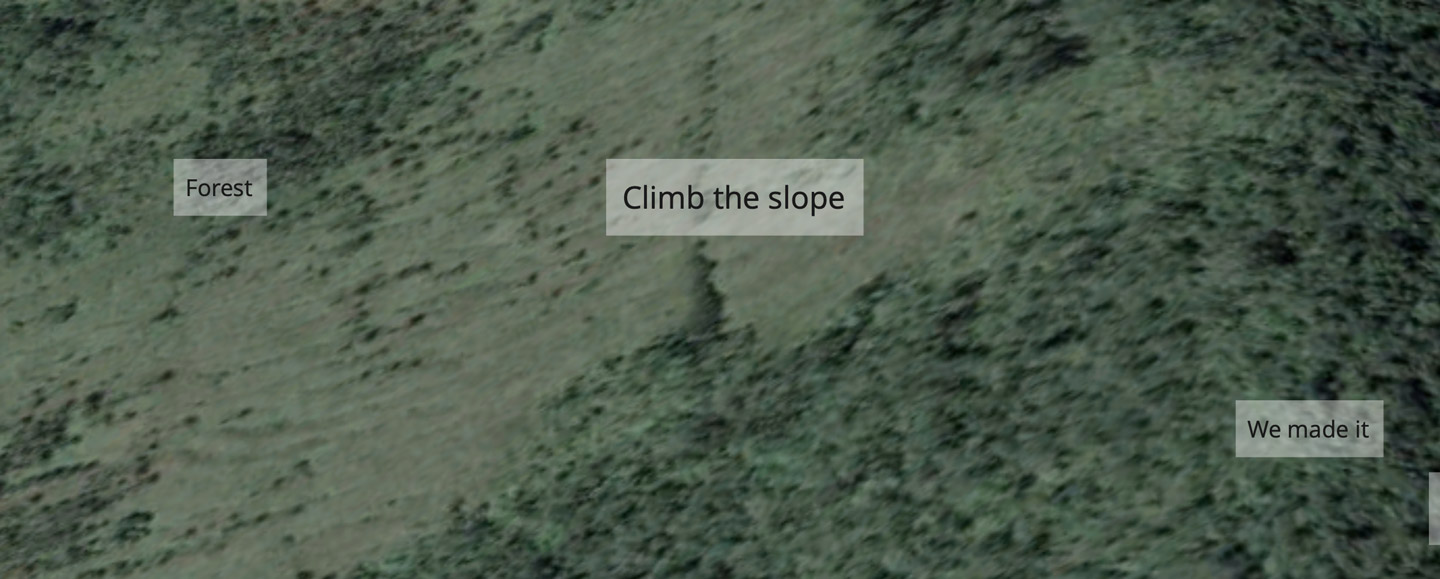

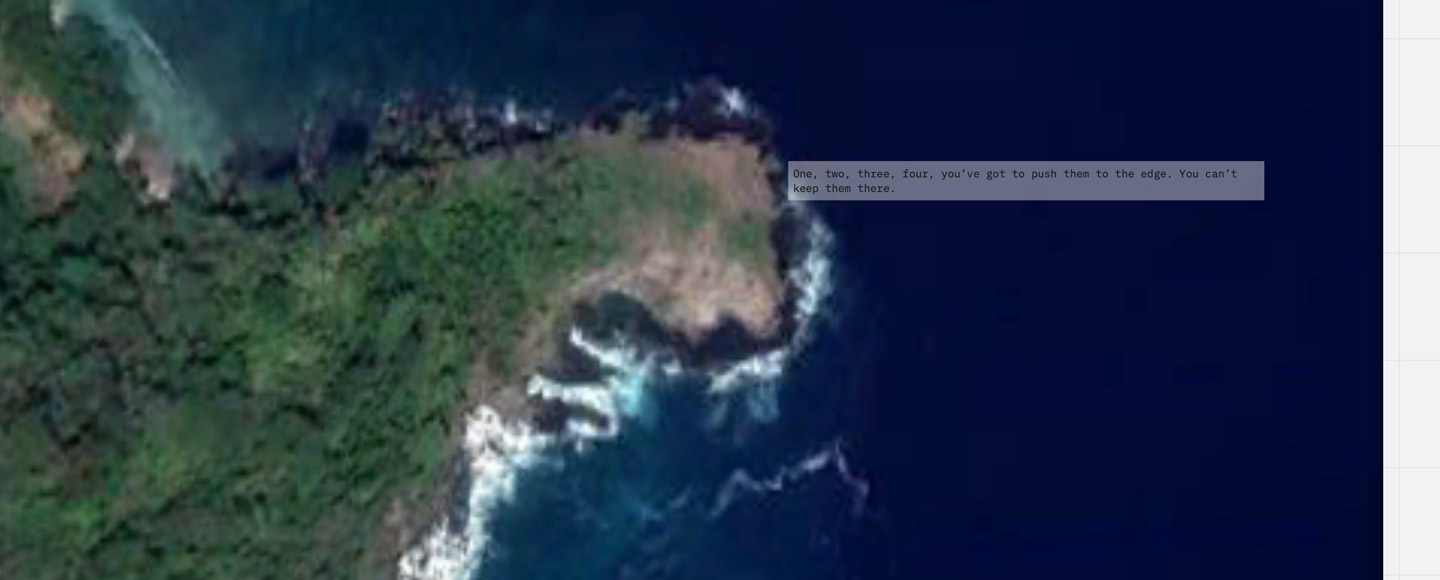

The viewer is taken by the hand by a macaque guide, who speaks through text blobs pasted on the images. By changing the font size of the text, the viewer is nudged to either zoom in or out.

The macaque guide and the viewer start off on a forested coastal area, but soon encounter human spaces. Although it is forbidden to hunt on wild animals, wildlife that exists outside national parks still suffers from poachers, as forest fragments are not protected [1,2].

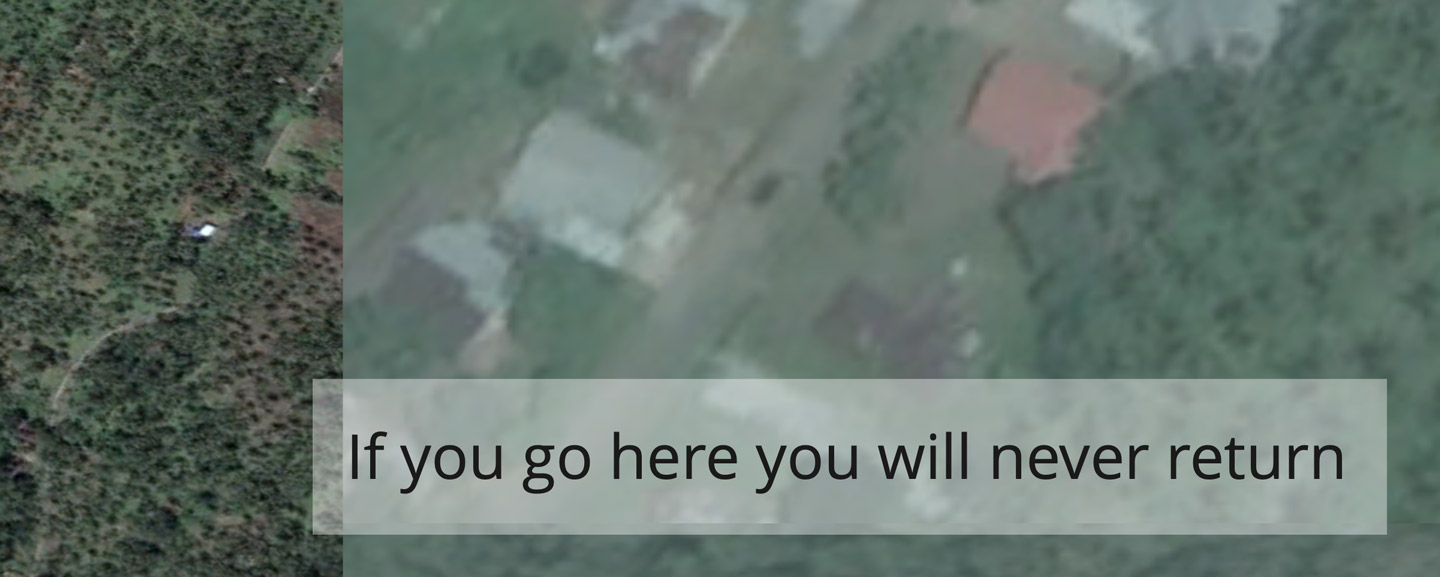

I aimed to leave the viewer with an uncanny feeling when approaching human land, by warning them (as the macaque) not to go into these areas. The guided tour ends in the ‘homeland’, a safe but small haven where the macaque guide will stay. The viewer can explore the area further at his own risk.

If the viewer embarks on an unguided exploration endeavour, he will find himself roaming an eerie and hostile place. Wandering through palm oil plantations, crowded settlements, and landscape-scarring gold mines.

Throughout this anthropogenic area are AI-generated texts from a (very critical) unknown nonhuman observer. I left these texts purposefully unedited, as I wanted to have a nonhuman agent (the AI model)*, to comment on ‘our’ use of the Earth. The vagueness of some of the responses added to the overall feeling of being lost and unsafe.

The additional Google Earth movie tour acts as a ‘proof’ for the content of the artwork: it shows that indeed, Sulawesi is largely dominated by human-made areas, and forests are only sparsely present.

* This admittedly is still is a human view, as it is humans who created both the content that the AI model drew from, and the AI itself.

Let me tell you a story from far far away

- If protecting natural habitats and animals is the answer, what is the question?

- If giving rights to non-human animals is the answer, what is the question?

- If sentientism is the answer, then what is the question?

- If deforestation is the wrong answer, then what is the right question?