The Other Mindsan artistic exploration of an octopus

Octopuses have nine brains. One in their head, and a small one in each of their arms. This leaves the single-brained animal wonder:

What is it like to be an octopus?

Parallel inner worlds

For all my life, I have desperately wanted to know what is it like to be another being. A nonhuman being. Since other animals are conscious too, we know it must be something like to be a soaring eagle, an echolocating whale, or a multiple consciousnesses possessing octopus. Yet we don’t have a clue what it is like.

It almost frustrates me, knowing that there are so many parallel inner worlds experienced by equally many nonhuman individuals, but that there is no way I can experience them, since consciousness is private.

What Is It Like to Be a Bat?

The question “What is it like to be a bat?” forms the center of the famous, similarly-titled article written by the philosopher Thomas Nagel’s (1974).

Nagel says, that when one tries to imagine what it would be like to be a chair or a stone, there will be nothing to imagine. Because stones and chairs do not experience anything, they are not sentient. But bats, for instance, do. They are organisms with conscious experiences.

Now the knowledge that it is something like to be a bat, doesn’t enable us to know what it is like. A bat flies and experiences input from an extra sense, echolocation, to navigate the world. Nagel argued that we will never be able to understand a bat’s experience: it would be as if a person who’s born blind will try to understand how it is to see.

In their article in the journal Animal Sentience, the philosophers Walter Veit and Bryce Huebner stated that:

The future of animal sentience research lies […] in empirically investigating what it feels like to be an echo-locating bat, an infrared-sensing snake, an octopus with multiple distributed ganglia, a fish without a neocortex, or an arthropod such as a spider or a honey bee.

…Yet, can we?

Is it even possible to empirically investigate what it is like to be another being?

I cast my doubts on it.

Consciousness is private and inaccessible for others. Even if it would be possible to know everything about another one’s brain, then still we would not have a first-person’s experience of their consciousness. We are a bunch of Mary’s in black and white rooms (que?).

So I wondered: how should we go forward, then, researching the consciousness of other animals? Because I still desperately want to know what it is like to be an octopus.

It got me thinking: if we cannot research the question What it is like empirically at this point in time, perhaps I can try to research it artistically. Perhaps I can explore other minds through sculpture.

So I made an octopus – the creature with the many minds – as an attempt to come closer to an answer to the question of What It Is Like to Be.

Why sculpture?

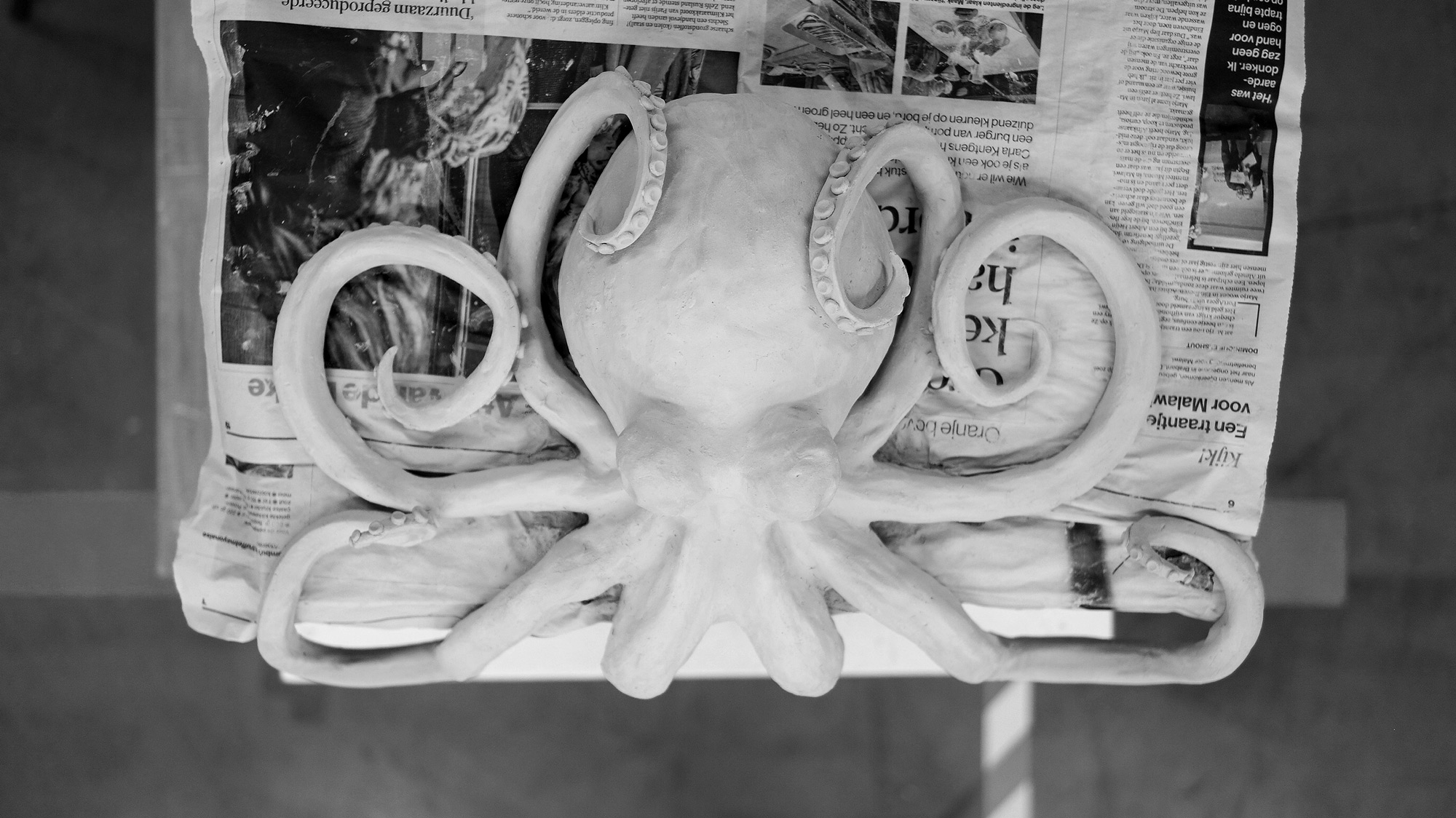

I think sculpture more than any other means gets me as close as possible to understand what it is like to be a certain being. It is very intimate to sculpt a creature, especially in the stage when it is getting form and you are positioning the limbs or sculpting the details of the face.

On some emotional level, touching the clay octopus’ tentacles feels like I am touching a (kind of) sentient being. As the clump of clay now has eyes, limbs and a recognisable body, it became someone. Carefully lifting a tentacle or kneading its round head into the desired shape makes me more sympathetic to the actual animal. I’ve always been fascinated by octopuses for their evolutionary story, but now I also feel more empathic to them.

Did this make me come closer to knowing what it is like to be an octopus? No. But it did make me empathise with the animal, through being able to create and touch its clay body. Through empathising (“inleven” – the Dutch word for empathising, literally translated as “living into”), we may come a tiny bit closer to understanding what it is like to be another creature, or at least having more compassion for it. So, art, in particular sculpture, may prove a valuable tool for expanding people’s moral circle to non-human sentient others. To be continued!

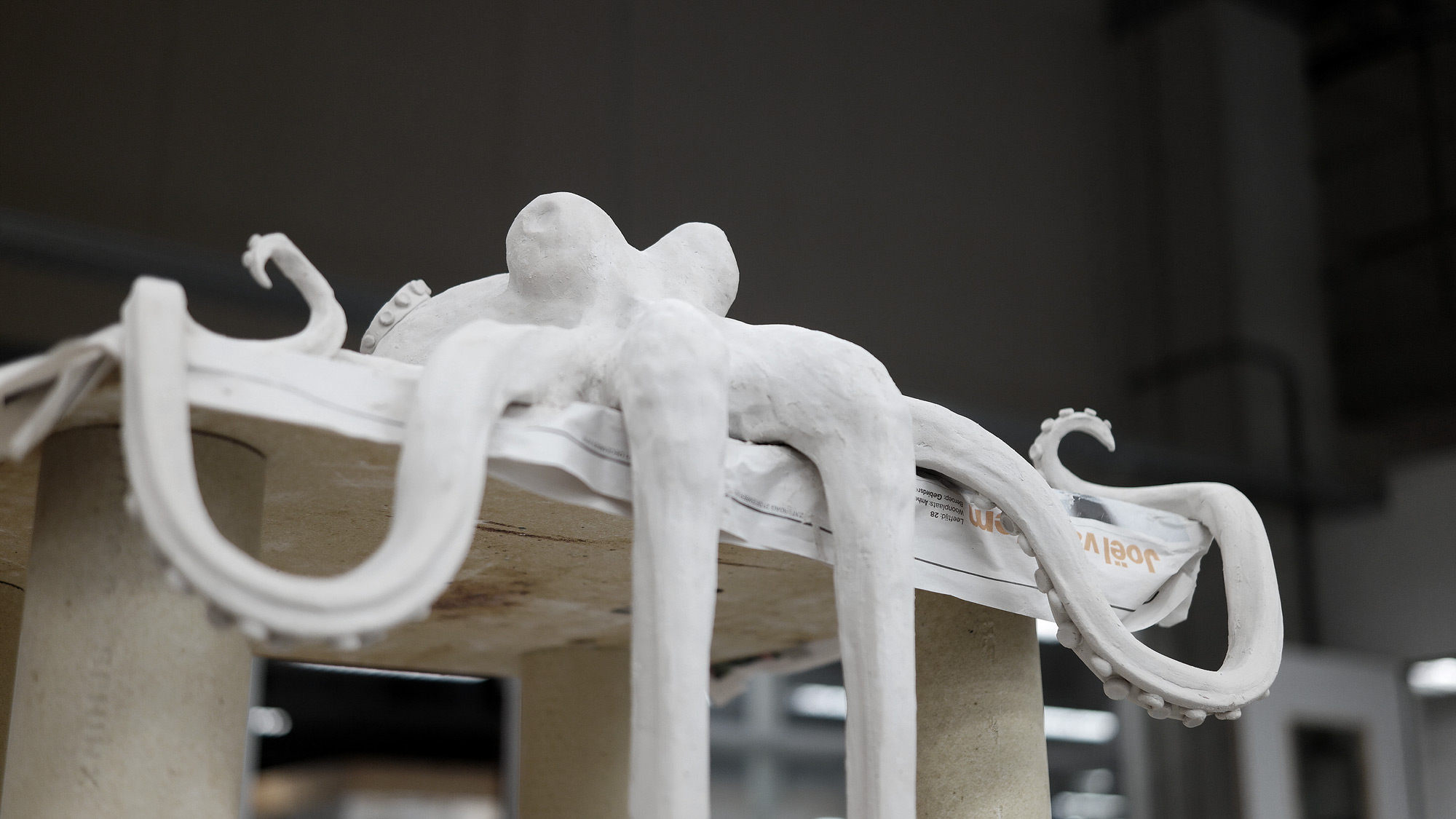

Here you can see the glazed octopus.